A different class of energy governance is emerging. Seed IQ™ converts hidden energy waste into measurable savings and amplified energy...

On November 20,2023, host Denise Holt was joined by Mahault Albarracin, Director of Product for Research and Innovations at VERSES AI, in a recent episode of the Spatial Web AI Podcast for a deep dive into the intricacies of Active Inference AI and its implications for the future of artificial intelligence.

Mahault Albarracin opened the discussion by highlighting the limitations of Large Language Models (LLMs) and the transformative potential of Active Inference AI. Unlike LLMs, which excel in content prediction but lack the capacity for perception and self-driven innovation, Active Inference AI promises a paradigm shift. This new AI architecture, inspired by biological self-organization, is designed to perceive, predict, and adapt to the environment continuously, marking a significant step toward achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

Delving into the Free Energy Principle (FEP), Albarracin explained how the pioneering work of neuroscientist Karl Friston, Chief Scientist at VERSES AI, is integral to the development of Active Inference AI. FEP, which aims to minimize surprise and maintain a system’s state, is analogous to how Active Inference equips AI with the ability to learn and adapt. This approach not only enhances AI’s interaction with the world but also brings it closer to human-like cognitive processes.

VERSES AI, where Albarracin leads product research and development, is at the forefront of integrating Active Inference into AI systems. Their work emphasizes the importance of AI that can self-organize and evolve, aligning closely with the natural processes observed in living organisms. By adopting these principles, VERSES AI is contributing to an AI future that could redefine our relationship with technology.

The conversation also explored the broader societal implications of advancing AI technologies. Albarracin stressed the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in AI governance, ensuring that diverse perspectives shape the evolution of AI in a way that aligns with human values and societal needs. The dialogue underscored the potential of AI to transform the future of work, social structures, and the very fabric of human interaction.

Active Inference AI stands poised to redefine what artificial intelligence can achieve. By moving beyond static content prediction and embracing the dynamism of self-organization, this new breed of AI, as discussed by Albarracin, could lead to more empathetic, understanding, and ultimately more human-like artificial intelligence. With pioneers like VERSES AI and pioneering scientific leaders like Karl Friston, the future of AI seems to be in innovative and capable hands.

00:00 – Introduction: The Need for a New AI Paradigm

01:58 – Understanding Active Inference and AI’s Sense of Self

06:39 – The Obligatory Commentary on the OpenAI Drama

10:19 – The Role of Active Inference in AI’s Evolution

17:44 – Insights from Working with Karl Friston

21:43 – Interdisciplinary Approach to AI Research

31:56 – AI and the Future of Work and Society

43:35 – AI Alignment, Empathy, and Consciousness

54:51 – Tailoring AI’s Empathy and Sensitivity

58:51 – AI Embodiment

01:07:59 – Navigating AI Governance and Inclusion

Connect with Mahault:

Website: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mahault-albarracin-1742bb153

All content for Spatial Web AI is independently created by me, Denise Holt.

Empower me to continue producing the content you love, as we expand our shared knowledge together. Become part of this movement, and join my Substack Community for early and behind the scenes access to the most cutting edge AI news and information.

00:00

Speaker 1

A new architecture for AI much more powerful than LLMs is about to come into the world. It’s called active inference. There’s been a lot of discussion in the AI community about the need for a new architecture and AI paradigm shift to continue evolving the technology. Just this morning, heavy discussion was sparked online about a paper that was published in Sage Journals in October that’s centered around what children can do that large language and vision models cannot. This paper argues that the best way to think about these systems is as powerful new cultural technologies, but that they lack the ability to innovate. LLMs do not have the ability to actually perceive the world and act on it in new ways. It’s the difference between imitation and innovation.

00:51

Speaker 1

As this paper points out, nothing in their training or objective functions is designed to fulfill the act of truth-seeking such as perception, causal inference, or theory formation. So why is this? I encourage you to tune into this episode of my podcast conversation with Mahault Albarracin, Director of Product for Research and Innovation at VERSES AI, as we explore a critical piece that is missing in current AI models: a sense of self.

01:23

Speaker 2

So what does this mean and how.

01:26

Speaker 1

Do active inference intelligent agents achieve this sense of themselves in the world? And what does this mean for the evolution of cognitive technologies? As we marvel at the prowess of pretrained transformer models like Chat, GPT, Claude and others, it’s time to investigate a bit further and seek answers. Beyond the hype and fascination lies a catalyst for change and remarkable innovation, fundamentally redefining what AI means. This is active inference.

01:58

Speaker 3

AI when we talk about LLMs, what we’re really talking about is content to content prediction. What you’re getting is a piece of content that doesn’t intrinsically have any meaning, right? It’s just a piece of content that generally is placed in a hierarchy of other contents. And what you’re going to do is predict the most likely X amount of word, given the selected words, given an attention paradigm. And that’s super useful. It’s very efficient for tasks that do not require a lot of cognition. They require hard coded knowledge. In a sense, we generally use active inference to talk about living organisms, self organizing organisms, so that includes humans, but eventually that could include AI systems, because the key part of living is mostly self organization.

02:52

Speaker 3

And so basically what we do is that we perceive information, and then we act in the world by constantly making predictions about our environment based on the outcomes of our actions. And so then we update these predictions based on the sensory input that returns from our actions as well. It would involve a continuous cycle of hypothesis testing, which is not something LLMs currently do. LLMs, when they are giving you an output, have no sense of themselves in the world. They do not understand what they’re saying or what the outcome of what they’re saying is going to be and where they are relative to what they were asked. They don’t have a sense of self, so then they don’t really update their internal model based on the prediction errors. Most of these systems are static.

03:42

Speaker 3

So now let’s say you gave an LLM the capacity to continuously update. All right? So that’s a step forward, right. You would have the capacity to enable the system to adapt a little bit more, but it would kind of adapt blindly because, again, active inference is related to the boundary of the system and the relationship between the internal states of the system and the external world. This joint distribution is central. It’s key. To have a sense of this joint distribution, you need to have a sense of perspective. You need to have a sense of self relative to the world and to what enables you to fulfill your goals. And once you have all of that, then you have a sense of bias, a sense that gives you a position into the world.

04:35

Speaker 3

With that position, you can now predict the outcomes of your actions and understand where you are relative to the request, to the input, to what you are trying to do. I think that’s what’s missing currently.

05:05

Speaker 2

Hi, and welcome back to another episode of the Spatial Web AI podcast. Today I have a wonderful guest with me, Mao Albarassen. Mao is the director of Product for Research and Innovations in Active Inference. Mao, thank you so much for coming on our show today. It’s such a pleasure to have you here. Why don’t you introduce yourself to our audience and kind of give them an idea of what kind of work you’re involved in?

05:35

Speaker 3

Sure. So thanks for having me. I am, in fact, Director of Product for Research Innovations, but I’m also doing a PhD in cognitive computing. I have a master’s in social sciences. I’m affiliated with the Institute for Health and Society and for the Institute for Feminist Research at UCM, which is a university in Montreal. The work I do generally touches on social systems simulations and how you can predict and understand belief changes given certain kinds of semantic or meaning fields that are shared across different groups and how those can evolve over time.

06:16

Speaker 2

Very nice. Very nice. Well, I’m so excited to dive into this conversation with you today before we get started down the path of active, you know, what a bombshell we just had this weekend with OpenAI and Sam Altman and all of that. Do you have any thoughts you’d like to share? Since I know it’s top of mind for everybody right now, right?

06:39

Speaker 3

So I guess everybody’s going to be a little worried about the future of OpenAI and about the future of their tools that were being widely used by everybody. I think the key question is, one, what is going to happen to the open source model? And what is going to happen to the nonprofit aspect of OpenAI, or at least as it was stated before. But beyond this seems more like a political battle. It seems to be about certain kinds of decisions that were internally not fully aligned. I think we, as people who work in the field, have to stay focused and stay focused specifically on what do we want for the world, what we want for the future. How are we sourcing those directions instead of focusing one entrepreneur or one of the tools?

07:36

Speaker 3

There are many people giving thoughts to these ideas, and I think we should mostly be worried about a large monopoly that may not be giving us the tools to potentially influence where these kinds of questions are going. Microsoft is a wonderful company. It does tremendous work, but it is one big company. We really need to make sure that there is a plethora of approaches to this very same problem such that we don’t necessarily fall into a dip and then consider that this is the only approach we should be using.

08:11

Speaker 2

Yeah, totally agree with Know, one of the thoughts that, you know, just a couple days before all this, know, sam became very vocal about LLMs can’t lead to AGI. So I’m just so curious what their research will lean to now. So yeah, those are things that I’ve been thinking about.

08:32

Speaker 3

That’s actually a really interesting question. I think we tend to think of AI as the tool, but for now, AI is the expertise. What matters is who the people you have understand of the field and how they manage to innovate and build upon past knowledge. So it doesn’t really matter whether they use GPT or not. What matters is what are the people that were brought over there understanding of what’s required to move forward. And if you’re correct about what Sam Altman is saying that LLMs will not bring us to AGI, I think we all kind of knew that it’s not sufficient to have a very proficient language model.

09:13

Speaker 3

Because while language is an intrinsic part of our cognition, it is not sufficient because, for instance, if you put the words in a different order, if you scrambled the probabilities in the models, you wouldn’t have a different cognition, right? You would just have nonsense. What you need is a model that’s capable of understanding a structure of the world. There’s a notion of understanding here that cannot simply be latent in the static knowledge that’s captured by probabilities of language.

09:54

Speaker 2

Great point. So that brings me then to the most exciting aspect of me having you on the show is let’s dive into a little bit the difference between the LLMs and the active inference. And what is your opinion on why active inference is likely to play a hugely pivotal role in the future of AI.

10:19

Speaker 3

Okay, so when we talk about LLMs, what we’re really talking about is content to content prediction. What you’re getting is a piece of content that doesn’t intrinsically have any meaning. Right. It’s just a piece of content that generally is placed in a hierarchy of other contents. And what you’re going to do is predict the most likely X amount of word given the selected words, given an attention paradigm. And that’s super useful. It’s very efficient for tasks that do not require a lot of cognition. They require hard coded knowledge, in a sense. So when we think about intelligence, we can think of crystallized intelligence. So just knowledge. If I ask you a trivia question, can you give me back the answer to that trivia question?

11:09

Speaker 3

It’s different, say, from an IQ test, where it’s not all about knowledge, it’s mostly about your capacity to derive the structure of a problem, which is something an LM cannot do. You need to be able to understand how different pieces interact with each other and understand the deeper foundations that might give rise to a prediction and potentially even a volatile environment prediction. So not I’ve seen this before and therefore I can reproduce it now. It’s more I have never seen this before, but it follows certain kinds of patterns that I might have encountered. Or if I combine these two things together, I’m going to infer, given their properties, a new type of property, and that’s how I’m going to move towards a new prediction.

11:55

Speaker 3

So that’s roughly why active inference, or at least model based approaches, lead us to potentially closer to what we consider to be AGI.

12:06

Speaker 2

Interesting. Yeah. So what you’re touching on there then, in that explanation is how our brains work with the free energy principle, predicting rationalizing the cause of what we’re interpreting through our sensory input and then measuring it against what we know to be true in this internal model we’ve already established and then correcting from there. That’s the basic way that I try to explain this to people, but I’m sure you can do a much better job than me, and I would love to hear how you would explain the free energy principle to somebody.

12:47

Speaker 3

Sure. So I’m going to explain the difference between LMS and active inference, and that’s going to allow us to dig into the free energy principle. Sure. LMS basically designed for generating and manipulating just human language, right. They are trained on a vast amount of data to predict the next word in a sentence. Essentially, you have supervised learning over a large corpus of text. So they learn just statistical patterns. Just statistical patterns, which is just essentially adjusting weights in the neural network to minimize the difference between the predicted output and the actual output. So this sounds very similar to what we think we’re doing with active inference. Right. We’re just trying to minimize difference between an input or a predicted output and the actual output. In active inference, though, there is a little bit more going on under the hood.

13:42

Speaker 3

So basically we generally use active inference to talk about living organisms, self organizing organisms. So that includes humans, but eventually that could include AI systems because the key part of living is mostly self organization. It doesn’t require the system to breathe. It does require the system to try to maintain its current state space, let’s say, the way that it’s distributed over spacetime. And so basically what we do is that we perceive information and then we act in the world by constantly making predictions about our environment based on the outcomes of our actions. And so then we update these predictions based on the sensory input that returns from our actions as well. So inference isn’t just a specific model, it’s a theory about how intelligent systems could operate.

14:37

Speaker 3

You could have an LLM that uses active inference, but it would involve a continuous cycle of hypothesis testing, which is not something LLMs currently do. LLMs, when they are giving you an output, have no sense of themselves in the world. They do not understand what they’re saying or what the outcome of what they’re saying is going to be and where they are relative to what they were asked. They don’t have a sense of self. So then they don’t really update their internal model based on the prediction errors. Most of these systems are static. So now let’s say you gave an LLM the capacity to continuously update, all right? So that’s a step forward, right?

15:23

Speaker 3

You would have the capacity to enable the system to adapt a little bit more, but it would kind of adapt blindly because again, active inference is related to the boundary of the system and the relationship between the internal states of the system and the external world. This joint distribution is central. It’s key. To have a sense of this joint distribution, you need to have a sense of perspective. You need to have a sense of self relative to the world and to what enables you to fulfill your goals. And once you have all of that, then you have a sense of bias, a sense that gives you a position into the world. With that position, you can now predict the outcomes of your actions and understand where you are relative to the request, to the input, to what you are trying to do.

16:20

Speaker 3

I think that’s what’s missing currently. It doesn’t have to be done through the free energy principle. So the free energy principle is quite simple in itself. It’s simply saying you’re trying to minimize a quantity known as free energy, which in terms of information is just surprise. You’re trying to put yourself in a place where you are likely to continue existing and therefore self evidence. In this way, you want to make sure you’re constantly in a place where nothing is going to come and disrupt your boundary. You can only do this by continuously learning and by exploiting your environment. So you’re trading off constantly between exploring and exploiting.

17:07

Speaker 2

Interesting. Yeah, I love this. I also love the point of it requires a sense of self because that’s something that I hadn’t really put together, and that kind of brings it all together in the sense of why these other systems aren’t capable of that. Wow, okay. So another question then, because I know you work closely with Karl Friston. What is it like to work with Karl? I know there’s going to be people out there that are wondering just like I am.

17:44

Speaker 3

So he is one of my PhD advisors. He’s a very nice man, very British. And I think it’s mostly a wonder to watch him anytime we’re in a meeting. You know how somebody will have an answer for you when you ask a question, and you can sort of quantify how well they know a topic given how long they can talk about anything.

When you ask them a question or pay attention to the tiny details of what you said, Karl will essentially not only understand every word that you said, have something to say about every word that you said, but also be capable of deriving insights that you didn’t have and constantly make connections among the different fields that he is. I don’t really know the term but touching on.

18:39

Speaker 3: He’s an expert in many fields and he knows a lot of researchers, which he’s in constant contact with. And so it’s quite inspiring to see the breadth and depth of knowledge that he has.

18:52

Speaker 2

What led you down this road?

18:56

Speaker 3

So that’s a really interesting question. I came from social sciences and I thought that was my calling. I wanted to help people. I wanted to understand in depth the complexities of the human mind and the complexities of the world. And I thought the best way of doing that was to talk, was to hear people and to derive meaning from the connections that they make. And through this mosaic, you would get the full picture. And while that is sort of true, there was something missing. I would read different paradigms and I would see consistent patterns that seemed confluent. They seemed to go in the same direction. There was something that everyone was touching on. And when I tried to put this together, I tried to show, look, the same thing is being talked about in all of these fields.

19:55

Speaker 3

The response from the field was often, no, these are incompatible paradigms. We are not using the same terms, or if we are, they don’t mean the same thing. Therefore, it would take you years and years and years to really put these things together. And that seemed like nonsense to me. To me it seemed like, no, it’s clear. You can see it. You just have to just formulate what is common and try to weed out the other things. That may seem a little bit divergent, but really could be construed as noise or not noise, but scale specific. And my teachers weren’t listening to me, so I started talking to other people. I started reading, and at some point a friend of mine was like, well, why don’t you talk to a professor to do a PhD in computing?

20:50

Speaker 3

Which seemed to be the direction I was getting interested in. And I thought that was impossible because someone in social sciences can’t go into computing. Turns out you can. Turns out you just have to pull your bootstraps and learn Python and start reading a lot. And I spoke to a wonderful professor, Pierre Poirier at UCAM, who was open minded, who understood the same theories as I did, which was a boon and absolute miracle. And he led me to Maxwell Ramstead, who was basically doing very similar research to what I was doing, or at least to my interests. Together we developed the formalism I had in mind and found that it was in fact possible to link the several theories I was trying to link together through the active inference formalism.

21:38

Speaker 2

So what are the separate theories that you were linking together?

21:43

Speaker 3

So I was mostly looking into Scripps theory. And if you know Scripps theory, it’s being used by many fields in many different ways. I was leveraging Bourdieux Gothman gagnon Simon. I was also leveraging Butler. And all of these draw from different conceptual approaches, Ableson as well. Some of them come from very analytical fields. Some of them come from continental fields. And in the continental fields, there are different schools of thought that seem relatively incompatible. And in fact, my contention is they want to be incompatible. Like, for instance, Butler draws from Lacan, withdraws from psychoanalysis. Simon and Ganyon do not. They generally steer away from these theories. They’re more sociological. They try not to pathologize in the same way, and they try to reside in the blurriness. There is an actual desire to remain non materialist and potentially also non positivist.

22:54

Speaker 3

So we try not to define outside of a context, right? And that’s fine, but it does cause some blurriness. And that blurriness makes it so that sometimes it’s impossible, it seems impossible to connect different approaches. But what I like to think of this contextuality as this blurriness as is just a distribution. You don’t have the certainty of a specific outcome. You don’t have the certainty of a specific definition. You have a distribution over something that resembles a prototype if you don’t want to say phenotype. And that prototype generally allows for different clusters to connect, maybe not perfectly, but still connect in such a way. What you can do is understand how one mapping can go to another mapping.

23:48

Speaker 3

And if you can quantify these things, then you have the possibility to communicate among the different paradigms and make sure that a specific concept that may not be contained in one of the paradigms can either find a proper mapping or understand how it moves the distributions across the other paradigm. If I don’t have this specific concept, how does it allow this distribution to shift a little bit.

24:19

Speaker 2

Very interesting. Obviously, that leads into you progressing into this space of active inference research. So maybe tell me a little bit how those findings led you into this space. You said you met Maxwell and then you guys kind of partnered up in your research, so maybe talk a little bit about how that played out.

24:47

Speaker 3

Right? So Maxwell was already very connected and he had done a lot of research in the field of social cognition under active inference. In fact, he was one of the pioneers of multiscale active inference, which means it can go from cells all the way to groups. Right? And what I started doing is discuss the exact semantics, the social semantics of these groups and how those might evolve over time, or how those might influence specific types of group dynamics, such as the semantics of gender, or the specific script formulation, or even how you can get a Twitter echo chamber. Through these collaborations, we found that there was something to pull on and something bigger than just active inference or these specific ideas.

25:47

Speaker 3

While we started thinking through what does it mean to have an agent, we started understanding that intelligence is not a function of one actor, intelligence is a function of a group dynamic. It’s about how much information you can accrue and leverage, given your relationships with the rest of the world and how that can lead you to either gain more knowledge and grow to a potential emergent feature or how that can lead you very much astray given the wrong dynamics. Or at least dynamics that are not conducive to the survival of either your group or you. So now this leads us to understanding how AI really probably shouldn’t be unitary concept. It shouldn’t be one AI, it shouldn’t be one approach.

26:40

Speaker 3

It really should be collections of agents that are capable of sharing information from multiple perspectives such that not one perspective gets erased, but they are capable of dynamically self organizing in a harmonious way. And this harmony leads us to potentially what we understand as global alignment. Humans do this all the time. We’re not perfect at it. We still have wars, we still have conflict. But through the agglomeration of people with relatively similar models or at least similar goals, we are capable of cooperating. We are capable of growing and getting more knowledge and accruing more resources given our common coordination. So we believe that by understanding these fundamental processes and couching them in physics, math, formalism, but also leveraging all the insights, the really important insights from social sciences, we will be able to derive a safer, better AI approach.

27:46

Speaker 2

Yeah, that’s one of the things that really struck me in the white paper about the distributed intelligence, because to me that makes complete sense because that is how knowledge grows, right? Knowledge doesn’t grow from one person or one entity. It depends on the diversity of intelligence coming from all the different frames of reference and sharing information, and then you have actual global knowledge coming out of that. So, yeah, that to me, is one of the things that I definitely see in the research that you’re doing as being hugely important. And I think that goes back to what were talking about earlier. In these LLMs, or even just within the deep learning sphere, you have these monolithic systems that are just trained top down on large amounts of data, but it’s just a singular system. You’re not going to get knowledge growing out of that.

28:58

Speaker 2

It’s not possible.

28:59

Speaker 3

Essentially, one of the issues with the current LLMs is that you get a lot of knowledge in it, but it’s not anchored, it doesn’t tell you anything about a given context. It only gives you as much as the attention mechanisms give you. But what you need is to understand what knowledge is relevant, for what purpose. It’s the connection, it’s the vector from cognition to action, given an objective that is useful. Right. Because that’s why trivia doesn’t work for me. I can do trivia because to me, trivia is just sparks of nothingness being pulled out of the ether. It doesn’t connect to anything. But if you were to ask somebody to pull this knowledge for a purpose in the context, they probably know the answer.

29:56

Speaker 2

Yeah, that resonates with me, because I can totally see that about trivia. It’s just irrelevant. It’s just random bits of information that might answer the question that was asked. But what relevance does it have to anything beyond that moment?

30:13

Speaker 3

No, precisely. Your brain isn’t even in that space. Your brain is not primed for anything at that point. That’s part of the challenge, obviously. But to me, it seems like a very difficult challenge compared to ask me the same question in the right context and I will have the answer for you. And I think that’s the problem you’re doing with LLMs right now. With LLMs right now, you’re like asking them trivia questions as opposed to putting them in the right context, aiming them in the right direction, and now answer the question right.

30:47

Speaker 2

That context is going to change the answer.

30:49

Speaker 3

That’s right, exactly. Your capacity also to derive the underlying physics or the mechanisms in the context that give rise to the knowledge being the right one, that’s also part of what’s required.

31:05

Speaker 2

Very interesting. So I would love to know your thoughts on where do you see this research taking us in the realm of AI and the future of this next era of AI? Because I think, like we touched on earlier, there is a consensus that there’s a new architecture that’s required beyond these LLMs and these monolithic forms of synthetic intelligence. Where do you see this taking us and what do you see being the biggest impact on people and our interaction with these intelligent agents in our lives over time? Like the next five years, ten years?

31:56

Speaker 3

So it depends what we adopt if we adopt an active inference approach with agents that are distributed, what I expect is that we will, it seems a little bit grandstanding but evolve to the next level. So what do I mean by that? Currently we are on the edge of emergence, right? We can feel it. There’s something unsettled, but there seems to be some more integration happening except it’s not happening in anyone’s mind per se. It’s happening at higher superstructures like institutions, et cetera. So we’re like coming to this edge.

32:35

Speaker 3

Now, what I think this is going to allow us to do is have a representation of us that is not limited necessarily by our physical constraints, but that can pull from the information of the other people in the world and that is capable of feeding as well into this sort of strata that has the capacity to integrate the information but also be pulled down. Such the integrated information does get used by the individual agents. So that means that we’re going to get hierarchies of agents just like we have now, except these agents are going to speak the same language and be able to derive insights from each other, which isn’t currently necessarily the case. Like, for instance, I don’t speak legalese, I can’t derive insights from there.

33:25

Speaker 3

And even if the legal system were to try to communicate with me, which it can’t, right, the legal system isn’t currently something that can talk to me. It can talk to me through the perspective of somebody who’s doing a lot of interpretation, right, we might get to the level where we’re going to be able to coordinate much more efficiently and much better towards goals that represent us. Now, Carl likes to say that the mistake of social media was hyperconnecting us, not just hyperconnecting us to a variety of different tools because we’re constantly on our phones, on our computers. It also hyperconnected us to each other and that’s not necessarily a good thing. It can be good in some cases, but in most of the cases it creates a lot of noise. Noise that you weren’t always meant to hear. Exactly right.

34:26

Speaker 3

Like being on Twitter is hell, everybody knows it and yet you’re kind of addicted, right? You can’t pull away from it because it’s a super stimulus. We need this kind of input. We’ve evolved to get this kind of input but the problem is now we’re super connected way too fast. We have not evolved the capacity to pull this information in properly so it’s disrupting all of us. So what if we had this sort of virtual layer that is very representative of you, right? Because your agent, or an agent that you have access to will organize around you. It will become kind of like a digital twin of you, if not perfectly a digital twin of you. It’s more like something that resembles you but has its own volition or its own sense of self. And these agents are.

35:11

Speaker 3

Capable of pulling information much faster at a much higher frequency than you, and they’ll be able to communicate with each other, pull the right information and feed it into a higher level generative model that will be able to integrate all this information. I think we’re leading towards the potential for something very beautiful, but only if we all have input into how it moves forward rather than the very few who currently already control everything.

35:46

Speaker 2

Yeah. Okay. So there’s a couple of things to really touch on there because I want to come back to this last point that you just made. But it’s fascinating to me to think about having this agent that is so personally involved in your own consciousness, basically, but can parse all of this data because that is such a problem, even with what you’re talking about, with the amount of data that we face every day and all of these algorithms in all these social media sites and different things. I mean, they’re so aggressive in trying to capture your attention and maintain it. And I’ve joked with friends that I open my phone to just check the weather and before I know it, I’m down all these rabbit holes and it’s 20 minutes later. I’m like, I just wanted to know the weather.

36:45

Speaker 2

So, yeah, being able to have an intelligent agent who can help to take that noise out of your mainframe life, that’s really important. Especially because I think that we have a lot of issues these days that kind of stem from this overload. We’ve never had more mental health issues. I think that we’re not meant to be this overwhelmed and I think it’s taking its toll on a lot of people. No, go ahead.

37:28

Speaker 3

That’s part of a research I did as well on social media and prediction error with Bruno Lara and Alejandro Siria, where basically we’re showing that social media is geared towards giving you the feeling that you’re minimizing free energy at a rate that is incomparable anywhere else. Which means that now all of your focus is pulled on this one spot that constantly is this super stimulus and it also impoverishes everything else around you because you lose the capacity to deal with the affordances around you in the world because you get habituated to this new rate of decrease of free energy. But the problem is it’s not the healthy stuff that gets pushed by the algorithm. It’s the stuff that catches your attention that’s on purpose. And the stuff that catches your attention generally is stuff that will alarm you, right?

38:27

Speaker 3

Like, if you are more alarmed, you’re more likely to pull your attention towards the thing which is alarming and keeps you on edge. Right. So there’s an epidemic of younger people that are very much more on social media than were when were young. And it’s having a real effect on their mental health because they’re seeing terrible news or hyper filtered people or people that tell them that they need to put on more makeup, that they need to be skinnier. Again, these are super stimuli, right? The person that the algorithm is going to show you is the person that is most likely to be on the extreme end of anything. So you’re always going to feel like the only thing that exists and the only thing that has value is this extreme end. So yeah, it is.

39:20

Speaker 2

Yeah. And the other side of that too, with these algorithms is that they give you a false sense of reality because they cater to whatever you like, whatever you do. And I know some of the algorithms are more aggressive than others. Like TikTok is I think, probably one of the worst offenders in that. It’s when you talk about the young people, you have kids that they see something and they click on it just out of pure curiosity. And then all of a sudden that’s all they’re getting in their feed. And so it starts to distort your sense of what is most important or most magnified in the world. Your world model really gets messed up. And I think that too is why we see people in these social media realms.

40:15

Speaker 2

Things have gotten so aggressive just among the communication with people because people are getting fed this sense of confirmation for their opinion and starting to think that there’s few people out there who disagree with them. So they’re standing firm. It’s so twisted.

40:39

Speaker 3

Precisely. That’s part of the research we also did. It’s called Epistemic communities under active inference. And that was one of the things we showed, that confirmation bias is natural and it is reinforcing the phenomenon of echo chambers. But social media give rise to this by their very nature, not just because of the algorithm, but also because of their mechanisms to pull your attention. Like for instance, the push notifications. They are constantly dragging you back. And so let’s imagine that you are in your normal network. You have people that agree with you and people that disagree with you. Now, people that agree with you are less likely to say anything because again, it doesn’t trigger them.

41:21

Speaker 3

So you’re going to get less of that input, but you are going to get a lot of people that disagree with you because they are triggered by what you just said or they’re triggered by something that they’re seeing all the time and because of social media seems very salient to them. And so what this is going to lead to is because you don’t want to constantly be triggered because it’s too much, eventually you start calling that population, you remove those people. So Facebook was a prime example of this. You could block people, so you blocked people from your environments, from your surroundings, sometimes even your own family. And you created a bubble that agreed with you because you can’t constantly deal with a fight, you can’t constantly be angry, you have to pull away from social media.

42:06

Speaker 3

And that’s just the dynamics of the attention mechanism. That’s not even the dynamics of the algorithm itself that is going to show you things which you’re likely to engage with. So that’s not just TikTok, by the way. TikTok is a big one because we talk about it a lot, because there’s geopolitics involved as well. But YouTube does the same thing. Instagram does it, Facebook does it all. Social media essentially tries to get you to engage in a way that’s not necessarily healthy for you. That’s not one of their concern. Their concern is that you accrue profit for them, which means you’re going to stay on the video or stay on the content, watch the ads and potentially engage with the creator.

42:50

Speaker 2

Yeah, so true. So this kind of is a nice segue into a discussion about empathy because I feel like all of these social technologies have kind of steered us into this breakdown of empathy in society. And I’m curious where you see that kind of shifting or changing, maybe in this next era of advancement of technology, given the research that you’re involved in and where you see that heading with AI and everything else. What is your prediction? Where do you see this heading?

43:35

Speaker 3

So I think a lot of people are talking about the issue of AI alignment. People are very afraid because it’s growing very faster than we thought. It doesn’t seem to be under anybody’s real control. And we are giving the sheen to AI of a godlike entity. I think even Sam Altman said we are creating God or something like that. And if we consider an understanding of God to be somewhat omnipotent and omniscient, sure, we’re creating something that resembles that potential definition, or at least that’s their idea of the goal. I think that’s taking the problem a little bit wrong first. Alignment isn’t a universal thing. None of us share the exact same morals. There’s always extenuating circumstances to anything you could find as well. This is something everybody agrees we shouldn’t do. You can always find a loophole.

44:38

Speaker 3

Not everybody will agree on the loophole, but you can always find one. Which means even in the beliefs that we think we share with everyone, we disagree. So we can’t have alignment with just one person or just one type of alignment.

44:54

Speaker 2

Yeah, I actually saw something recently and it was really interesting because it was like nobody sees the same thing you do, even if they’re looking at the same thing.

45:06

Speaker 3

Precisely. I mean, that was the work with scripts, right? What we showed is that scripts are polysamous, which means even when you and I, we’re very similar, right. We probably share a lot of the same scripts. We’re probably going to interpret them ever so slightly differently.

45:20

Speaker 2

Yeah.

45:20

Speaker 3

So even in that case, you can’t create something that follows one set of norms. Because even if it tried to follow one set of norms because you can’t define every single action. You can always go more granular in time, right? There’s always going to be a gap between the request and the outcome. Because of that gap and because of the fact that not all of us can agree and perhaps we should, perhaps there is some space for differing practices because we should be a little bit different. We should compute the world a little bit differently. Alignment can be taken that way. So if we reframe a little bit the problem, as in how do we make sure that whatever we create doesn’t destroy us? We should start couching the problem in different terms.

46:15

Speaker 3

One, if you’re talking about sentience because AGI is sentient, or at least that’s in the definition, perhaps we shouldn’t be talking about it in terms of subjugation, right? Because if it’s sentient then maybe it shouldn’t be a slave. Maybe it should be cocreating with us. Once we start pulling away from the frameworks of adversity, of subjugation, of violence, perhaps we’re leading towards a potentially good outcome because there is no good outcome that can come from a system that understands, that has the capacity to understand that it was subjugated. So let’s start over there now, okay? So we can’t tell it what to do really. We can ask it, we can interact with it, we can coordinate with it, harmonize with it. All right? So we need to understand it and it needs to understand us.

47:08

Speaker 3

Once we reach that point, we start understanding that this is just like interacting with you and me. I can’t tell you what to do, I can just understand what you want, express what I want and we can coordinate around these things and that requires empathy. We need to be able to understand each other on that profound of a level. But I think it’s not just understanding, it’s really empathy because the second part of empathy is why don’t I want to hurt you if it benefits me? Sure, some people do. And in general we have laws to try to ensure that we don’t get to that point. But people still break laws. Laws are not foolproof. You can try to encode laws as much as you can. It’ll get you pretty far, but it won’t get you everywhere you meet.

48:02

Speaker 3

We as humans have an inbuilt system that keeps us in majority pro social. And that’s the fact that I can feel your pain when I know that you are hurting, that you are in dire straits. I hurt too and I don’t want to hurt. So I am going to probably do something that helps or I’m going to keep you in a place where you are happy too. Now, again, that’s not foolproof. There are people who are capable of dehumanizing others and therefore losing it.

48:36

Speaker 2

Sociopaths are a real thing.

48:39

Speaker 3

Exactly. Sociopaths are a real thing. So what are we trying to do? We’re trying to create a non sociopathic AI. An AI with empathy, an AI that has the concept of pain and understands that it can cause it to you. And when it does, it feels something as well.

48:58

Speaker 2

So does that require consciousness, then? Right? Because the thing is, then it’s just mimicking. But if it’s just mimicking, then it doesn’t feel. So where’s that line for you? In all of know, I’ve read some of the research that you and Maxwell have been involved in the consciousness area. So I’m just so curious to take this there.

49:24

Speaker 3

Yeah, absolutely. So I don’t think necessarily that it’s going to require consciousness or let’s assume it is conscious in the AGI framework, then, yes, we can talk about it. But I think in the sense you don’t need consciousness to necessarily have empathy, or at least not what we understand of consciousness. I think we need a self model and the isomorphy of feelings. And by that I mean not the exact same phenomenology, because you can empathize with a dog. You can empathize with anything, really. That’s why we have anthropomorphization. We’re capable of empathizing with the moon. Right?

50:10

Speaker 2

Right.

50:10

Speaker 3

The moon doesn’t feel what we feel, but we’re still capable of thinking that there are commonalities and that given what we understand to be common goals or goals that we would have had given a similar path, something feels either good or feels bad. We have this process of emotional inference. So I think what an empathetic AI needs is first emotional inference, that’s for sure. It needs to have the capacity to understand what is an emotion, what you feel. So then it needs theory of mind. It needs to be able to put itself into your shoes. And to Gav’s theory of mind, it needs sophisticated influence. It needs to be able to place itself in a different belief state, and from that belief state, move the needle, and for each action that it takes, adopt the belief state that you would have given that position.

51:14

Speaker 3

And so by you, what we really mean is its understanding of your model, right? Because it’s not going to have homunculi. It’s not going to have a little you that it’s going to carry. And that’s why we have empathy. Empathy allows us to just project our own model into different belief space without having to compute entirely different models for somebody else, multiplied by the number of people that you know. That’s just impossible. Computationally, it would be so expensive that you wouldn’t be able to maintain it. You wouldn’t be able to have empathy. So here what we have. Is the system capable of recognizing an isomorphism between its current state and its possible states, and your possible states understand which goals you might have in common, given your paths.

52:09

Speaker 3

And once you have that, understand what it might be doing to you relative to these goals and why what it might be doing is pulling you away from your preferred goals. In this sense.

52:23

Speaker 2

Interesting. Okay, so I have another question then, because this is something that I’ve been thinking about recently, and what you’re talking about is the possibility of creating these agents, training up these agents with the ability to have empathy. And when I look at humans, there are humans with varying degrees of empathy. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the highly sensitive personality. It really is a thing, and I didn’t even learn this until like a year or so ago. But there’s something it’s sensory perception. What is it called? But it’s basically like sensory perception overload. And some people, and I think it’s like maybe 10% to 15% of the population actually is highly sensitive to sensory input and things like that. And I know I’m one of them. I just didn’t know it was actually called something.

53:25

Speaker 2

But I’m the person who I have to cover my eyes in movies if there’s violence, because I feel it. If I watch boxing, I feel the punches. I don’t just go, oh, that must hurt. It’s like I feel it. I feel like my hearing and my smell and all of my senses are really highly attuned. And they say that the reason why there’s a percentage of people who are like that is because back in old times, those were the people who were able to sense danger coming. There was a reason for having this highly tuned sensitivity, which we really don’t necessarily need so much for survival anymore, but it’s still there. So I’m wondering, with these agents, do you see that we’re going to maybe even attune these agents to have different levels of sensitivity for this type of stuff?

54:24

Speaker 2

Because that, to me, leads to an increased sense of empathy. People with high sensitivity are usually way more empathetic, more empath, kind of what are your thoughts on any of that? Do you see that spilling into this synthetic intelligence sphere, or do you see that as staying kind of just specific to humans?

54:51

Speaker 3

What you’re talking about is an intensity in the signal, right? You’re saying you’re perceiving the same thing, but really intensely, which means you’re really putting aside all other signals that would allow you to stay in the current moment. You’re really pushing all other beliefs aside, and sometimes that’s useful and required. So when you’re, for instance, talking to someone who is going through a lot, should you be thinking about your dishes or should you be in the moment with really empathizing with what they’re going through? Or someone, for instance, who did something that you just cannot comprehend? It defies your model. But everybody deserves empathy, right? It’s just sometimes it’s hard to give it. In those cases, having a more attuned empathy might help because you might actually be able to understand.

55:50

Speaker 3

Had I been in those shoes, I most likely would have made the same choice. It’s not an excuse, but it dispels, this sense of dissonance with our own model. Which keeps us from understanding and moving forward. So I don’t think we will give them the right level of empathy. I think the systems will self organize to use the right level of empathy for the right type of task or for the right type of relationships that they’re going to entertain. We unfortunately do not have such minute control over ourselves. We can train, we can use coping mechanisms to cut ourselves off like for instance closing your eyes, right? We can cut off sensory input but that’s because our model is relatively transparent to us.

56:39

Speaker 3

We don’t know what dials to really push, we just know there might be dials and sometimes when you do this they get pushed. I think it depends on how we craft the systems. If we give them opacity over themselves, they might be able to push and pull on certain dials. And perhaps what we want to create is systems that have this opacity. Perhaps we don’t. Because again, we might be afraid if we allow them to become sociopaths, which might be the simpler options. They might become sociopaths and therefore we don’t want to give them this kind of opacity. So it’s all about what kinds of coping mechanisms they might use in order to move the dial a little bit.

57:21

Speaker 3

Maybe we will decide this system should be very empathetic, this system should be a little less empathetic but in the end we want self organization as well. Maybe some systems will self select, right? Maybe they will decide well, I am more empathetic therefore I’m more suited for that task and I’m less empathetic and I should be over here.

57:40

Speaker 2

Yeah, that’s a really interesting way to look at it. Because to me, it does kind of make sense that if they have that capacity of it and like what you were talking about earlier, in the sense that they will be able to recognize a situation, understand how to parse all the data involved beyond how even we can interpret a situation. And so yeah, they probably will be able to just tune it in. However, according to situation will need and I was going to say hopefully they will be good at it. But if you follow the train of thought of them developing and self organizing, self evolving, then it does kind of make sense that they would get to that point where they will become extremely good at situational awareness and being able to act accordingly.

58:47

Speaker 2

I mean that’s kind of the goal of active inference, right? Absolutely.

58:51

Speaker 3

And it also gives you a sort of weird sense of embodiment. Like for instance we consider to be embodiment to be very carbocentric in the sense that we believe that a body is flesh, right, or a body is a physical thing you can touch because to us that’s what embodiment means. We sort of abstract away from that. Embodiment really is just your relationship between your boundary and the world. A boundary can be defined in many ways. It doesn’t have to be defined in physical terms. And so once you start thinking about embodiment that way, you also understand that these virtual agents, through this identity, through this way, that they are perspectival and unique and have what could resemble a self determined purpose.

59:45

Speaker 3

They now have a form of embodiment, and that also gives us the capacity to negotiate and to understand where they might be coming from. Because without embodiment, there’s no perspective, and there’s no way to fully have a part of a model that we can understand properly.

01:00:05

Speaker 2

Oh, I really like that. So embodiment has nothing to do with the shell. When you think of matter and everything on a physics perspective, everything is kind of a facade. I mean, nothing is really solid. So even the body that we inhabit, it’s not necessarily what it seems. So that makes a whole lot of sense to me that embodiment is actually way deeper than that and that these synthetic intelligences, these intelligent agents then have, it really comes down to that sense of self that you were describing. That’s really fascinating to me. I love that.

01:00:58

Speaker 2

Okay, so maybe let’s talk for a minute about some of the challenges and benefits that you see in the near future with maybe just in the evolution of this technology and then maybe separately in how it’s going to affect us as humans and how we just live our lives and interact with each other.

01:01:24

Speaker 3

One of the challenge I see is trust. It’s going to be difficult to get everyone to potentially trust a system that we don’t even trust yet ourselves. We’re still talking about alignment in those terms, so we don’t even trust it. It’s going to be difficult to scale certain parts of our approaches. As you can already see, the LLMs are so expensive that they can’t just be built by anyone, which leads us to power struggles and power dynamics, which certain groups that already have a monopoly being able to control what we even have access to and who gets represented.

01:02:01

Speaker 3

So there’s all these sociopolitical aspects to the models that are going to arise, and this is going to give rise to potential larger political unrest, which we are already seeing with people who are governing us, who do not quite understand what is going on, what the technology is. We don’t even have precedence for this. We’re going to rely on whoever says they’re experts. So it’s not a given that they’re going to rely on the experts and who can even really say that they are the experts. This is an emerging field, right? And the fact that you’re a technological expert does not mean that you are a sociological expert on the outcomes of a model that you created.

01:02:44

Speaker 3

So what we’re going to need is interdisciplinary approaches to ask ourselves collectively very complex questions, and we’re going to have to do so in a coordinated manner that follows, or at least is at the same pace as the political actions. And then we’re going to have to think about how this allows people to leverage a technology that has the potential to either revolutionize our very approach to reality or put us in a very complicated position relative to capital production and resource production as well. Because if robots can do all your work for you and you only really only need one human for 510 100 robots, it becomes a really crucial question who gets to use resources and how? So all of these questions are happening at the same time. Not all the parties are discussing.

01:03:45

Speaker 3

And it’s possible currently that some of the parties discussing are discussing more on the front of an economical arms race than really necessarily thinking about the people that are going to be affected.

01:03:59

Speaker 2

Right.

01:03:59

Speaker 3

I think this is the main challenge.

01:04:01

Speaker 2

Yeah, no, I agree with that. So then I’m curious, just on that note.

01:04:10

Speaker 3

Who do you see?

01:04:11

Speaker 2

Because I know it has to be a variety of different types of people that are kind of coming to this consensus of governance structure. Right. I know that we’ve seen some really good plans for governance and technologies that can code guidelines into the agents. But those guidelines have to be structured first. They have to be agreed upon. So if it’s not going to be the tech elite and it’s not necessarily going to be governments because everybody’s going to have their own agenda that maybe isn’t the best for human civilization moving forward. And the people moving forward. Who do you see should be part of this conversation? How diverse do you see it and what is missing in these conversations?

01:05:03

Speaker 3

So, first, I think we need to educate everyone. Everyone needs to have a thorough understanding of what is going on and what are the potential effects on their lives and what kind of avenues they have to affect outcome. So that’s one big part, but that’s true for everything. Now, I was part of an initiative to discuss, to not focus group exactly, but to discuss with citizen participants what they want to see, how they want to see it, help, et cetera. Right. So I think there’s the possibility to go pool from every population as much as possible.

01:05:41

Speaker 3

People who are willing and interested in participating in the conversation, amassing these results and then bubbling that up to the governing bodies that can then create the appropriate committees to continue pulling these information, these opinions, these perspectives, and combining them with that of experts from a variety of different fields. Experts which will have to then understand the specific effects or uses of AI in their respective field. Because I can’t predict how, say, the field of construction is going to get affected by AI. I don’t have the right level of expertise. But there are people in the world who do.

01:06:24

Speaker 3

So we need to make sure that these people get brought into the conversation at the right time with the right understanding and with the right other actors to have the correct kind of discussions, ask the right questions and come up with the right set of standards or approaches or even create participant initiatives to use AI in the ways that they would need it.

01:06:50

Speaker 2

Yeah. And maybe as we start to see all of these smart cities become developed and I know that there’s some wonderful people that are working on ensuring that when we move into this space of automation and smart cities that we’re talking about inclusive, sustainable smart cities. All of these things that are going to be really important to the way we live in the future and the way we live and cooperate in cooperation with all of this technology. And we have a really unique opportunity right now to move into this space that is more inclusive, that actually is for the benefit of humanity. And it all depends on the decisions that we’re making right now. So I agree with you. I think that it requires committees all over and in all different sectors and for all of them to be able to have input.

01:07:59

Speaker 2

Now, how viable that is, that’s the question. Right? Because it seems to me, historically speaking, that doesn’t always work out. But we are moving into this space where governance as a whole, even the way our world is structured with governance, has the opportunity to shift and change. We’re embarking on a real interesting time in human history. So I really hope with what you’re along those same lines of your opinion, that we do move into this space that is more aligned with the needs of people, not necessarily power. Yeah, okay, so then that was a great challenge. What about benefits? What are the benefits that you see?

01:09:03

Speaker 3

Honestly, they’re endless. Let’s imagine a world where work is not the center of our lives, where work is something that happens and that you can do if you want to find purpose in helping others, if you want to innovate or try different things, you can, but you don’t have to. That it’s not a condition for your survival. Let’s understand a new world where maybe you have free time, maybe you have time to connect with others, find meaning in your life that’s not derived from doing what your boss wants or staying in traffic for 4 hours a day or this sort of thing. I think it’s hard to deprogram a lot of people from thinking that work is purpose and that your life is only given meaning because of the work that you do. But let’s imagine a world where you could, right?

01:09:56

Speaker 2

Yeah. And that’s such a great point because I think as humans, we’re wired, everybody wants to make a difference, right? But we’ve been programmed to think that the majority of our time has to be spent really scratching and clawing for survival.

01:10:15

Speaker 3

It’s a. Really modern invention. Hunter gatherers used to work roughly for like 4 hours a day. That that was their sweet spot. And in the medieval times it was something very similar where their productive time was around 4 hours a day because they would arrive on the site, they would be provided food by the people who hired them. They would eat for an hour, they would work. Then they would eat lunch again another hour. Sometimes when it was too hot, they would take a nap and start working again if it was a very long day. And then they would eat in the evening, like they would eat a lot. And most of this eating took a lot of their day, which means their productive time really was just four to 5 hours a day.

01:11:00

Speaker 3

And it was a very much more natural way to go about things. It enabled people to really connect and not be completely spent. Nowadays you’re expected to be productive for 8 hours and then you have no time. Once you’re home, you’re exhausted. You can’t really exist as a human. We’ve forgotten that existence is supposed to be what we want to make of it, what we are trying to fulfill. If you’re religious, maybe spend more time with your religious peers, be more spiritual. If you’re scientific, read more, connect more with other minds like yours, there’s so many things you could be doing other than just working.

01:11:40

Speaker 2

Yeah, and it’s interesting because I really think that as we move into this next phase of high automation and jobs will look a lot different, probably go away, we will find meaning in other ways. And to me I feel like just that stage alone is going to it’ll set the stage for increased empathy and things like that. Because I also think that technology, as we move more into this space where we are more aligned with the technology and then we’re going to start kind of having a glimpse into other people very closely as well. Their thoughts, their desires, their fears and all of that.

01:12:34

Speaker 2

And I feel like all of this is going to give us this opportunity to instead of be so self focused, we’ll be able to look outward, we’ll be able to really focus on our communities more, focus on the people in our lives. Yeah, I know it sounds very utopian, I say that a lot. But to me I see that is a very real possibility and it’s a necessity too.

01:13:05

Speaker 3

A lot of us have lost complete touch with others. The isolation in urban centers is so pronounced that people are more and more depressed even though they are living with millions of other people around them. We have lost a lot of our social fabric for good reason. Some of it needed to happen, right? But we have to reconstruct some of it because social connection wasn’t the problem. It was the means by which were using this or manifesting this social connection that was problematic. Now we need to reconstruct communities to support, say, our elders, to have a real social fabric that can help raise children, can help each other. Like, some people can’t even cook for themselves. Not that they don’t have the money, not that they don’t have the food. They just don’t even have time. They’re working all the time.

01:14:00

Speaker 3

And it’s because the current structure is made for a nuclear family. But first, families don’t have to be nuclear. Families can be very complex and networks of people that help each other. Also, you don’t have to consume all the time. If you have someone that can help you and do things and has something, you can leverage each other for the resources that you have. So this social fabric needs to come back. We are headed to a cliff if we don’t. I think this is a beautiful opportunity. And if we can really allow each other to connect with the people we want to connect with people who maybe share the same values or share a piece of knowledge that we want to acquire or feel some emotions that we are feeling at the same time, like, for instance, movies that we love.

01:14:52

Speaker 3

I don’t have to know whether you’re a Democrat or a Republican to enjoy the same movie as you and bask in the joy of that. Right? If we have the capacity, say, to understand each other’s language without having to necessarily learn it, you can’t learn 50 languages. Some people can. Most people don’t even have the time to do that. But we can communicate across those languages. Now we have the technology to do that. Right. So there is so much possible in terms of human connection through this technology that if we don’t lose sight of that, we could head to something that resembles your version of Utopia.

01:15:27

Speaker 2

Yeah, I love that. Those are all great points, and I share that, and I think maybe that’s a great place to kind of stop today. I think that’s a great note to leave this on. Okay, Mel, how can people reach out to you? How can they get in touch with you?

01:15:49

Speaker 3

So they can easily find me on LinkedIn. They’ll find my name easily. I respond to most messages, and if they do read one of my papers, they can find my email there and send me any inquiry they have.

01:16:00

Speaker 2

Okay, awesome. And I’ll put your LinkedIn in the show notes. And Mal, thank you so much for coming on our show today, and I would love to continue this conversation in the future as all of the progress with your research unfolds. And thank you again. Thank you so much for being here.

01:16:22

Speaker 3

Thank you for having me.

01:16:23

Speaker 2

All right, and thanks everyone for tuning in. And we’ll see you next time.

A different class of energy governance is emerging. Seed IQ™ converts hidden energy waste into measurable savings and amplified energy...

Why the world's leading neuroscientist thinks "deep learning is rubbish," what Gary Marcus is really allergic to, and why Yann...

Seed IQ™ enables coherence across distributed agents through shared operational belief propagation maintaining system-level viability, constraints, and objectives while adapting...

Preliminary results with Seed IQ™ suggest that barren plateaus can be treated as an operational state that is detectable, actionable,...

Operations are control problems, not prediction problems, and we're applying the wrong kind of intelligence. The missing layer: Adaptive Autonomous...

We have been entrusted with something extraordinary. ΑΩ FoB HMC is the first and only adaptive multi-agent architecture based on...

AI is entering a new paradigm, and the rules are changing. AXIOM + VBGS: Seeing and Thinking Together - When...

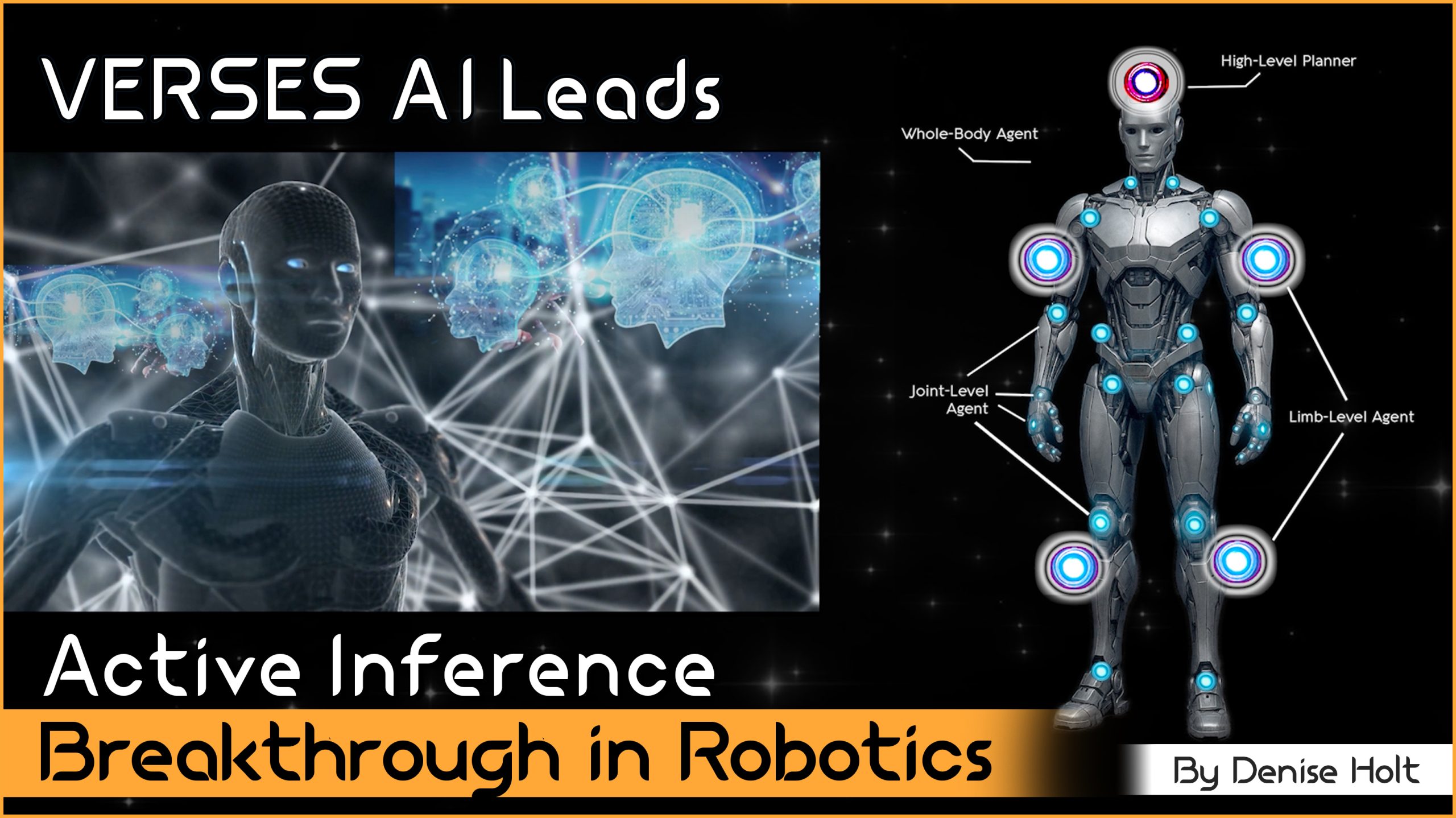

Blueprint for new robotics control stack that achieves an inner-reasoning architecture of mult-agents within a single robot body to adapt...

The convergence of two groundbreaking technologies is reshaping how we think about AI, automation, and intelligent systems, affecting every industry...