Active Inference & Spatial AI

The Next Wave of AI and Computing

Supply Chains Don't Need Better Forecasts - They Need Execution Intelligence

- ByDenise Holt

- January 16, 2026

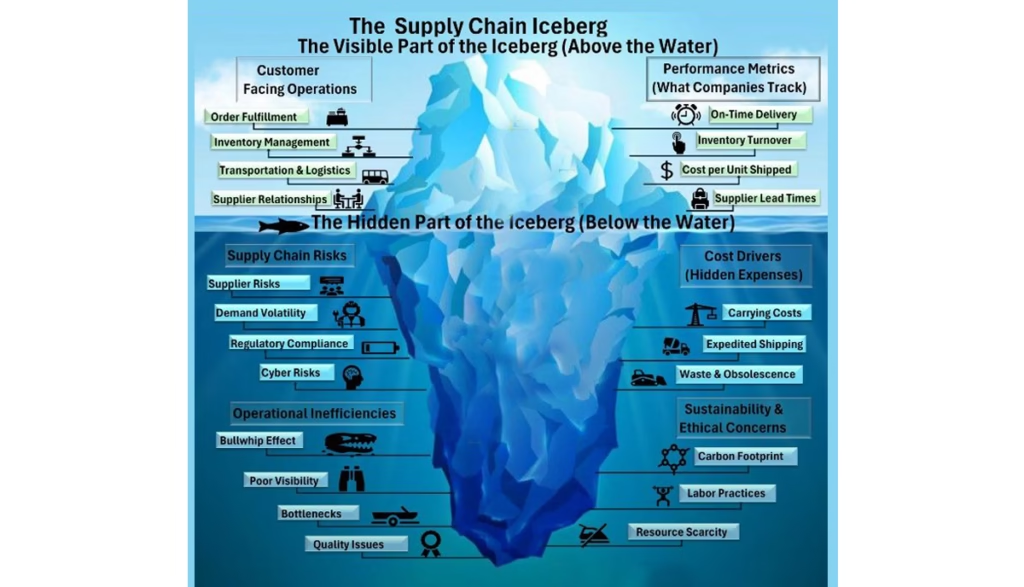

Global supply chains are among the most complex operational systems humans have ever built. They span continents, cross legal and regulatory boundaries, depend on thousands of independent actors, and operate under constant uncertainty. Materials, information, capital, labor, weather, geopolitics, and demand signals all interact continuously, often in ways no single organization fully controls or even sees.

For decades, enterprises have invested heavily in tools designed to make supply chains more efficient. Forecasting systems predict demand. Optimization engines compute routes and inventory targets. Dashboards surface KPIs. Automation accelerates execution. Each of these advances has delivered measurable value.

Yet despite all of this sophistication, global supply chains remain fragile. Disruptions propagate faster than organizations can respond. Local optimizations routinely produce global breakdowns. Rare events dominate outcomes. And when failures occur, they often emerge slowly, invisibly, and expensively.

The issue is not a lack of data or analytics. It is a mismatch between the kind of intelligence supply chains actually require, and the kind of intelligence most systems are built to provide.

Supply Chains Are Living Systems, Not Static Networks

Supply chains do not behave like static graphs that can be optimized once and then left alone. They behave more like living systems. Conditions change continuously while execution is already underway. A port delay cascades into warehouse congestion. A supplier shortfall amplifies transportation bottlenecks. Labor availability shifts mid-week. Weather events alter transit reliability without warning.

In practice, this means supply chain decisions are rarely isolated events. They are part of long-running processes that unfold over time under uncertainty. By the time a plan is evaluated, the context that justified it has already changed.

Most existing AI systems are not designed for this reality. Forecasts are generated at discrete intervals. Optimization runs assume stable constraints. Exception management reacts after thresholds are crossed. Human operators are expected to bridge the gap with experience and improvisation.

This approach works until it does not. When variability increases and coupling tightens, the gap between plan and reality becomes the dominant source of risk.

Failure in Supply Chains Is Usually a Trajectory, Not an Event

When supply chains fail, they rarely fail all at once. They drift.

Inventory builds in the wrong locations while shortages appear elsewhere. Transportation networks remain operational but increasingly misaligned. Expediting costs rise gradually. Service levels erode quietly. Teams compensate locally, masking systemic issues until recovery becomes difficult or impossible.

By the time failure is recognized and apparent, the system has often crossed into a state where corrective action is expensive, disruptive, or no longer effective. This is why so many supply chain crises feel sudden in hindsight, even though the warning signs were often present for weeks or months.

Traditional AI systems are not built to recognize this kind of drift. They focus on detecting anomalies or optimizing short-term metrics. They ask whether something looks unusual or whether a specific decision improves performance right now. They do not ask whether the overall execution path remains viable.

What supply chains need is intelligence that can assess trajectory health continuously, not just flag isolated deviations.

These Are Not Logistics Problems. They Are Operational Invariants.

What makes this challenge difficult is not that supply chains are uniquely broken. It is that they exhibit the same structural properties now appearing across the most demanding operational environments.

Execution unfolds continuously under uncertainty. Decisions are made while conditions are already changing. Failures do not announce themselves as discrete events. They emerge as gradual loss of viability. Costs accumulate long before outcomes are visibly wrong. And by the time traditional controls react, the system has often crossed a threshold where recovery is no longer clean or inexpensive.

These characteristics are not specific to logistics. They appear wherever operations are distributed, tightly coupled, and exposed to variability. Domains with thinner margins reach these limits sooner, but the underlying invariants are the same.

Supply chains are now operating beyond the point where prediction, optimization, and post hoc exception handling can govern execution reliably. What is required is intelligence that can remain engaged throughout execution, recognize when trajectories are becoming unsafe, and intervene before drift becomes collapse.

Worst-Case Outcomes Matter More Than Average Performance

In supply chain operations, average performance metrics can be deeply misleading. A network that performs well most of the time but fails catastrophically under stress is not resilient, nor reliable. A few extreme events can erase years of incremental efficiency gains and erode trust.

Executives understand this intuitively. The real cost of supply chain failure is not captured in average lead times or forecast accuracy. It appears in missed market windows, damaged customer opinion, contractual penalties, regulatory exposure, and long-term brand impact.

Managing supply chains effectively therefore requires explicit attention to worst-case behavior. Intelligence must be able to recognize when low-probability, high-impact risks are accumulating and intervene before those risks dominate outcomes.

This is fundamentally different from optimizing averages. It requires governing how the system behaves under stress, not just how it performs under normal conditions.

Adaptation Must Occur During Execution, Not After the Fact

Supply chains do not pause so models can be retrained or plans recalculated. Ships keep moving. Production lines continue running. Orders flow through systems even as conditions change.

Any intelligence that requires retraining, redeployment, or manual reconfiguration in order to adapt is already too slow for real operations. By the time the system updates, the situation it was designed to address has often passed.

Instead, what is required is the ability to adapt during execution, within explicit operational boundaries. This does not mean improvising without constraints. It means adjusting behavior in real time while preserving coherence, safety, and alignment with enterprise objectives.

Adaptation without governance creates chaos. Governance without adaptation creates rigidity. Supply chains need both at the same time.

Distributed Operations Require Coherent Distributed Intelligence

No modern supply chain is centrally controlled in practice. Decision-making is distributed across procurement teams, logistics providers, warehouse operators, transportation networks, and automated systems. Each actor operates with partial information and local objectives.

Traditional coordination approaches rely on centralized optimization or explicit orchestration logic layered on top of this complexity. These approaches struggle as scale increases. Centralized systems become slow and inflexible. Rule-based coordination breaks down as scenarios escalate and compound.

What is missing is a way for distributed components to remain aligned without constant micromanagement. Intelligence must be able to propagate shared operational understanding across the system so that local decisions reinforce global objectives rather than undermine them.

This requires coherence, not just communication.

Supply Chains Need Execution Governance, Not More Recommendations

Many AI tools in supply chain promise better recommendations. They suggest alternate routes, revised forecasts, or optimized inventory targets. These tools are helpful, but they place the burden of judgment back on humans.

In environments where conditions change continuously and consequences compound over time, recommendation alone is not enough. What is required is governance of execution itself.

Execution governance means maintaining an ongoing understanding of whether current operations remain viable, when adaptation is warranted, and when continuation no longer makes sense. It means being able to intervene early, explicitly, and safely rather than reacting after damage has occurred.

This is not about replacing human judgment. It is about giving organizations the ability to manage complexity at a scale and speed no human team can sustain alone.

Seed IQ™ is Designed for Multi-Agent Operational Control.

Seed IQ™ (Intelligence + Quantum) is designed specifically for environments like global supply chains, where intelligence must operate continuously across many distributed actors, each making decisions under uncertainty, while remaining aligned with system-level objectives.

What Coherent Multi-Agent Control Looks Like in a Real Supply Chain

Consider a common disruption scenario. An upstream supplier delay begins to compress inbound schedules. Port congestion increases dwell times. Warehouse capacity tightens downstream. None of these events are catastrophic on their own, and no single system has full visibility into the combined effect.

In a traditional supply chain stack, each part of the system reacts independently. Forecasts are revised. Alerts are triggered. Transportation expedites. Warehouses reshuffle inventory. Procurement adjusts orders. Each response is locally rational, yet collectively they amplify congestion, cost, and instability.

Under an adaptive multi-agent autonomous control layer, the system behaves differently.

Each operational agent maintains a bounded understanding of local conditions while participating in a shared belief about overall execution viability. As constraints tighten, belief about what remains feasible propagates across agents. Routing decisions adjust. Commitments are paced. Certain flows are constrained or temporarily halted before congestion cascades into systemic failure.

No centralized replan is issued. No problematic rule set is invoked. Local autonomy is preserved, but global coherence emerges through shared belief rather than command.

Instead of attempting to force execution to continue under degrading conditions, the system governs whether continued execution remains viable at all. Adaptation occurs early, explicitly, and safely, containing disruption before it compounds.

Governing Distributed Execution Through Coherent Autonomy

In practical terms, a supply chain is not governed by a single decision engine. It is governed by thousands of decisions made across procurement, manufacturing, transportation, warehousing, fulfillment, and external partners. Each decision is locally rational, yet collectively these decisions can push the system toward instability if they are not coherently aligned. This is where most supply chain technologies fail. They optimize locally, then attempt to reconcile outcomes after the fact.

Seed IQ™ approaches this problem differently. Rather than issuing centralized commands or relying on symbolic coordination rules, it enables coherence across distributed agents through shared belief propagation. Each agent operates according to Active Inference principles, maintaining its own understanding of local conditions, constraints, and objectives, and adapting its behavior continuously as observations change. At the same time, those agents operate within a shared operational belief field that encodes system-level viability, constraints, and allowable actions.

This means that when conditions shift in one part of the supply chain, such as a supplier delay, port congestion, or transportation disruption, the implications of that shift propagate through the system as changes in operational belief rather than as discrete alerts or commands. Downstream and upstream agents adjust behavior organically, not because they were instructed to do so, but because the shared understanding of what remains viable has changed.

This form of coordination is fundamentally different from messaging-based orchestration or centralized optimization. There is no fragile control logic attempting to reconcile competing objectives after conflicts arise. Coherence is maintained continuously, as part of the mathematical structure of how the system reasons, rather than being enforced externally. Local autonomy is preserved, but it is bounded by the same operational reality across the system.

From an operational perspective, this enables capabilities that traditional supply chain systems cannot provide. The system can recognize when execution paths are drifting toward non-viable states even when individual metrics still look acceptable. It can intervene early by reshaping behavior across multiple agents simultaneously rather than reacting to failures one node at a time. It can explicitly manage worst-case exposure by constraining how risk accumulates, instead of discovering risk only after it materializes.

Just as importantly, Seed IQ™ can determine when continued execution no longer makes sense. In supply chains, this might mean halting or containing certain flows, suspending commitments, or preventing further amplification of loss. Safe halting is not an operational failure. It is an expression of control that preserves all options and prevents cascading damage.

The result is not a smarter plan. It is a supply chain that can govern itself under uncertainty. One that adapts continuously without retraining cycles, without fragile or unreliable orchestration, and without relying on humans to detect systemic drift after it is too late.

At the same time, coherence across the system is maintained through belief propagation rather than centralized command or symbolic coordination. Local autonomy and global alignment coexist.

Seed IQ™ is an adaptive multi-agent intelligence layer designed to govern how supply chain execution unfolds over time under uncertainty.

When Execution Is Governed, Economics Change

The most immediate impact of governing execution rather than merely predicting outcomes is economic. Supply chain failures are expensive not because they happen, but because they are allowed to propagate unchecked. Costs accumulate silently as misalignment spreads across inventory, transportation, labor, and contractual commitments. By the time disruption becomes visible, recovery is already operating in a loss-maximization regime.

- Execution governance changes this dynamic fundamentally: When a system can recognize that an operational trajectory is becoming non-viable, it can intervene before loss compounds. This might mean rerouting flows early, suspending commitments, containing exposure in specific regions, or halting execution paths that are no longer worth pursuing. These interventions are not reactive fixes. They are deliberate acts of control that preserve optionality.

- The economic effect is a shift from cost amplification to cost containment: Instead of absorbing cascading losses across multiple layers of the supply chain, organizations can bound downside early. Instead of discovering failure after capital, inventory, and goodwill have already been consumed, they can make explicit decisions about when to continue, when to adapt, and when to stop. This turns uncertainty from a source of runaway cost into a managed variable.

- Just as importantly, predictable downside enables more aggressive upside: When organizations can bound worst-case exposure, they gain the confidence to automate more decisions, experiment more freely, and operate closer to optimal capacity without fear that a single disruption will spiral out of control. Governance does not slow operations. It accelerates them by making risk legible and manageable.

- This is why execution governance is not merely a resilience improvement. It is a competitive advantage: Enterprises that can govern supply chain behavior under uncertainty recover faster, commit capital more confidently, and operate with higher throughput during disruption. Over time, this compounds into superior service reliability, lower structural costs, and greater strategic flexibility.

The shift is subtle but profound. Supply chains stop being systems that must be protected from volatility, and become systems that can operate effectively within it.

Digital Twins Emerge When Execution Is Governed

Much of what is currently labeled a “digital twin” in supply chain technology is still observational. These systems visualize state, replay historical data, or generate forecasts, but they remain external to execution. They do not act, adapt, or bear the consequences of being wrong.

A real digital twin is a continuously running inferential system that exists in lockstep with the thing it represents. It does not just observe state. It infers causes. It anticipates futures. It acts back on the world and updates itself based on the consequences of those actions…That single requirement already disqualifies deep learning. — Denis O.

A true digital twin must operate continuously alongside the system it represents. It must maintain an internal understanding of state through time, infer causes rather than just report metrics, and influence execution as conditions change. That makes digital twins fundamentally a control problem, not a modeling or analytics problem.

When supply chain execution is governed through adaptive autonomous control, digital twins stop being mirrors and become counterparts. Seed IQ™ provides the control layer that makes this possible by enabling continuously running, bounded, multi-agent inference across operational systems. In that sense, digital twins are not a separate technology category. They are an emergent property of governed execution.

Operational Control as Competitive Advantage

Global supply chains have reached a point where incremental improvements are no longer enough. The complexity, speed, and interconnectedness of modern operations mean that failure modes are no longer isolated or obvious. They emerge gradually, propagate silently, and become expensive before they become visible.

This is not a failure of effort or investment. It is a structural limitation of the kinds of intelligence most organizations have been deploying. Prediction, optimization, and automation have taken supply chains far, but they were never designed to govern global execution under persistent uncertainty across distributed systems.

What is now required is a different layer of intelligence. One that can remain engaged across systems of execution. One that can maintain coherence across autonomous actors without centralized micromanagement. One that can recognize when trajectories are becoming unsafe and intervene before disruption becomes inevitable.

Supply chains do not need more recommendations. They need the ability to govern behavior as conditions evolve. They need intelligence that understands not just what is happening, but whether what is happening still makes sense.

Organizations that implement adaptive autonomous control now will operate with a fundamentally different advantage. They will see instability earlier, adapt faster, contain disruption more effectively, and turn uncertainty into a controllable variable rather than an existential risk. They will define how complex operations are governed, while others continue reacting to systems they no longer fully control.

As supply chains continue to grow more complex, adaptive multi-agent autonomous control will become a baseline requirement for competitive operations. This shift is already underway.

This article is the third in a series examining what enterprise operations require from AI. Supply chains make the challenge visible at scale. They show how distributed execution, continuous disruption, and tightly coupled decisions expose the limits of prediction and optimization.

In the next article, we turn to energy systems, where those same dynamics operate under hard physical constraints. Stability cannot be deferred, rerouted, or recovered after the fact. Execution must be governed continuously, or it fails.

If you’re building the future of supply chains, energy systems, manufacturing, finance, robotics, or quantum infrastructure, this is where the conversation begins.

Learn more at AIX Global Innovations.

Join our growing community at Learning Lab Central.

The global education hub where our community thrives!

Scale the learning experience beyond content and cut out the noise in our hyper-focused engaging environment to innovate with others around the world.

Join the conversation every month for Learning Lab LIVE!